On September 13th, Sweden booked their ticket for the next round of the Davis Cup when they faced Tunisia in a World Group I playoff tie at Partille Arena in Gothenburg.

Ironically, 22-year-old Leo Borg, the son of Swedish legend Bjorn Borg, won the deciding rubber 50 years after his legendary father gave Sweden its first overall Davis Cup win, when they defeated Czechoslovakia 3-2 in the final in 1975.

While father Bjorn back then took some of the first steps towards launching Sweden as a superpower in tennis, Leo’s win in Gothenburg offered a very rare glimpse of hope for a nation that has experienced a remarkably rapid fall from grace since Sweden dominated world tennis on the men’s side for decades between the 1970s and 2010.

Golden generations

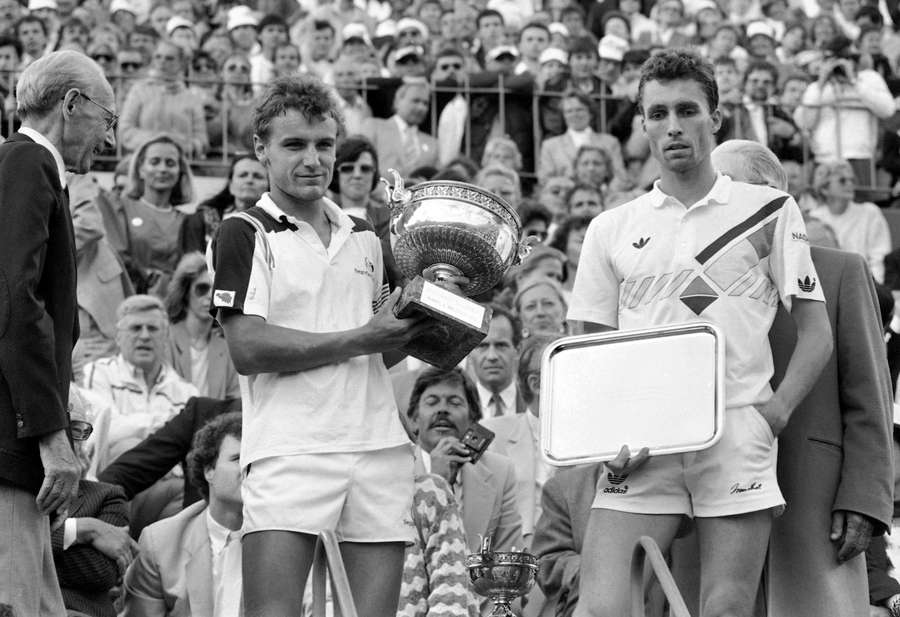

Bjorn Borg, Mats Wilander, and Stefan Edberg spearheaded golden Swedish generations, which also included Anders Jarryd, Joakim Nystrom, Henrik Sundstrom, Kent Karlsson, and others, as 26 Swedes born in the 60s managed to enter the Top 100. Nine of them reached the Top 10, and two of them belong among the greatest players of the Open Era.

From 1974 to 1992, Swedish men won no less than 24 of 76 Grand Slam events. In 1988, Swedes swept all four majors, with Edberg winning Wimbledon and Wilander claiming the other three.

But although they did manage to win three Davis Cups in the 1990s, Sweden’s success at Grand Slam events came to a sudden stop after 1992.

Today, Thomas Johansson’s surprise 2002 Australian Open victory is the country’s sole major triumph in the last 21 years.

Thomas Enqvist, Magnus Norman, and Robin Soderling reached Grand Slam finals, but when Soderling, one of the few players to beat Rafael Nadal at the French Open, was hit by mononucleosis and was forced to end his career, there was no one there to carry on the torch.

Swedish tennis grew complacent

In 2023, no Swedish players finished the season in the top 100, and currently, no Swedish woman or man is ranked inside the world’s top 200.

According to Mats Wilander, Swedish tennis declined because other nations learned from Sweden's golden era and surpassed it, while Sweden failed to invest enough in player development, coaches, and resources, and grew complacent after its historic success.

Simon Aspelin, Swedish Davis Cup coach, says in an interview with Flashscore that "when tennis turned into a global sport and competition got tougher and tougher, Swedish tennis failed to develop at the same pace."

Aspelin points out that Sweden, these days, is facing several challenges to produce players capable of sustaining themselves within the top 100, both on the men’s and women’s sides. One of those challenges is that the country simply doesn’t offer enough facilities for tennis-interested youngsters.

Politicians fail to prioritise sport

"If you look at the Stockholm area, we don’t have enough courts or facilities, and it’s the same problem with the rest of the big cities in Sweden. Politicians don’t prioritise providing facilities for sports enough. It's not only a problem for tennis but also for other sports," explains Aspelin.

Magnus Norman, who was second in the world rankings in 2000, the same year he reached the final of the French Open, agrees with Aspelin and said in an interview with tennis.com that while recreational tennis is popular, the country lacks the high-performance facilities needed to develop elite players, especially considering the long winters that require indoor courts, which are expensive.

Sponsors needed for additional tournaments

Another challenge is the low number of tournaments staged in Scandinavia. Sweden hosts two major annual tennis tournaments, featuring both men's (ATP) and women's (WTA) events, though the WTA event is a lower-tier tournament.

In addition to one ATP Challenger Tour event, the Good to Great Challenger in Danderyd takes place on Swedish soil, while various ITF and Tennis Europe events like the M25 Varnamo and W35 Bastad tournaments give Swedish talents few opportunities to test themselves against the world elite on home soil.

The lack of elite tennis tournaments in Sweden puts an enormous financial strain on Swedish talents and, not least, their parents and the federation for travelling expenses to attend tournaments abroad in order to earn points for their rankings.

"Of course, it would be easier if we had the same tournament schedule as Italy, where you have Futures and Challenger tournaments pretty much every week, mixed in with ATP events.

"But Futures and Challenger tournaments are quite expensive to operate, so they need cooperation from potential public or private sponsors," adds Aspelin.

The welfare state poses problem

While the Swedish population benefits from a social democratic welfare state with free schooling, health insurance, and protection from unemployment financed by taxes on workers and employers, it's not necessarily an advantage when it comes to developing young Swedish talents into world-class athletes.

"In Sweden, it's mandatory to go to school, at least through ninth grade, and it's of course great that you have something to fall back on. But modern tennis is very demanding, and requires early and intense dedication, and that might sometimes be difficult to mix with the Scandinavian views of having a balanced childhood.

"For instance, if you compare us to Eastern Europe with the sacrifice and commitment they put into developing young players, we must realise that that is what we are up against," says Aspelin.

With Nellie Taraba Wallberg placed in 13th place and Lea Nilsson in 24th place in the girls’ junior world rankings, while William Rejchtman Vinciguerra features as no 34 and Ludvig Hede no 50 in the boys’ junior world rankings, there is hope that this former Scandinavian tennis giant can rise from the ashes.

However, if this is to happen, Swedish tennis must have a better structure in terms of what programs should include when players transition from junior to senior tennis.

Plan missing for transition to senior tennis

"We have promising juniors both among the girls and the boys, but we haven’t been able to develop them in the next phase into Top 100 players.

"The challenge is that we are a relatively large country with many clubs with competition programs, which in one way is good, but the quality is not good enough to make them ready for the next phase.

"Clubs need to be clearer about what the options and the pathways are for young players, and we need to have a better plan for what the program for youngsters needs to deliver on.

"Players actually don’t pay so much for training in Sweden because either the training is reduced or they get it for free. If you go abroad, it's different because the parents or the players know that they have to pay to invest in becoming a great player.

"There is a clearer picture abroad on what programs need to include, and what the commitment from the player should be. And that is why in Sweden, when you go from being a junior to playing on tour, it's an enormous transition," concludes Aspelin.